What is a peal board?

Well, before this commission in 2022 I'd never heard of one either. Making it gave a chance to see a tiny glimpse of something that most people outside of bell ringing never see. In this post we go up the stairs in the church tower, through a small door and into the bell loft to have a glimpse at the hidden world of the bell ringers.

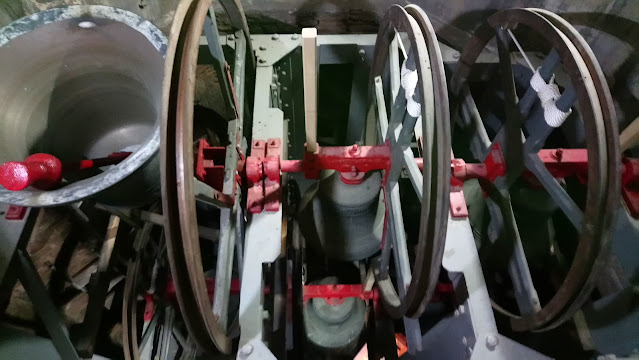

Bells are traditionally rung to call people to worship in Christian churches in Britain. Ringing developed from the use of a single bell to several, which are rung in complicated patterns that require a lot of skill from all participants to play accurately. Each ringer in the tower will play a single bell by pulling on a rope to make it swing, so that the sound fits in with the pattern being played.

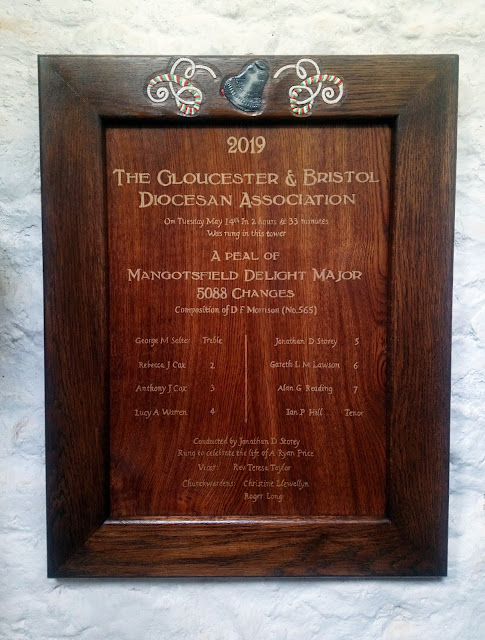

A peal board is a wooden panel made to record special sessions of bell ringing. These sessions may last for two or more hours and are done very occasionally to commemorate particular events or people, usually having a close connection to that church or bell ringing group. The board shows information such as who rang the peal, what pattern was rung and who or what was being commemorated amongst other things.

The commissioned board was made from a solid oak panel fitted into an oak frame and will be hung alongside others in the bell loft, where the ropes used in ringing hang down from the bells above. You can see some other boards and bell ropes in the picture above, along with images of previous bell ringers and Tower Captains (head bell ringers) associated with the church of St James, in Mangotsfield on the edge of Bristol.

After going out through another small door, we had a fine view from the tower over the surrounding houses to the Gloucestershire countryside beyond.

The oldest peal board in St James goes back to 1922, when the bells were first installed, although some in other churches are apparently much older. The one I made will be there for as long as bells are rung in the tower and I'm sure that, given its particular interest to certain people, would be a collector's item after that. It occurred to me that these peal boards are important documents of the history of ringing in that bell tower.

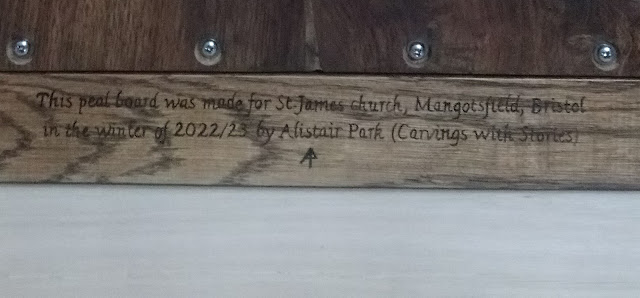

I wanted to carve and paint part of the design to record this so, after discussions with Jon, the frame now features an image of the actual tenor bell which hangs above it, along with bell ropes and sallies (the wider, colourful grips on the ropes) in the colours of the ones presently in the church. There is text painted on the reverse of the frame recording who made the board and where it was originally hung.

I wonder who will be surprised, after taking down the panel perhaps hundreds of years from now, to see this text. What will the world around them look like by then?